“COMFORT WOMEN WANTED” and “Re-creation of a Military Comfort Station” bring to light the memory of 200,000 young women, referred to as “comfort women,” who were systematically exploited as sex slaves in Asia during World War II, and increase awareness of sexual violence against women during wartime.

This project is based on my interviews with survivors in 7 different countries in Asia, including Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Filipino, and Dutch “comfort women” survivors, as well as a Japanese soldier from WWII.

Presented nationally and internationally including at The Incheon Women Artists’ Biennale (Korea), The Comfort Women Museum (Taiwan), 1a Space Gallery (Hong Kong), The Kunstmuseum Bonn (Germany),The State Museum of Gulag (Russia), The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History (Korea), Hauser & Wirth Gallery (New York), Spaces Gallery (Cleveland), The Boston Center for the Arts (Boston), The Charles Wang Center (New York), George Mason University Gallery (Washington DC), Glendale Central Library (CA), and Wood Street Galleries (Pittsburgh). Public Art throughout New York City including in Times Square, Lincoln Center, and Chelsea – in collaboration with The NYC Department of Transportation’s Urban Art Program.

Supported by The New York State Council on the Arts Grant, The Asian Women Giving Circle Grant, The Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s MCAF, The New York Foundation for the Arts Fiscal Sponsorship, The Korean Ministry of Gender Equality & Family Award, The Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant, and The Asian Cultural Council Fellowship.

Lectures & Screenings including at Columbia University, UC Berkeley, Stanford University, UCLA, Emory University, Wellesley College, Brandeis University, The University of Arizona, UC Riverside, The China Institute, Georgia State University, The City University of NY, The Korean American Association/The Consulate General of the Republic of Korea in Atlanta, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and The Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, The Kupferberg Holocaust Resource Center and Archives, The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, The Korea Society, and USC Shoah Foundation.

Featured including in The New York Times, The Huffington Post, Art Asia Pacific, The Korea Times, The Taipei Times, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Morning Brew, Dazed & Confused Magazine London, Emaho Magazine, NPR, KBS TV News, and The BBC.

“World War II Sex Slaves Bear Witness” The New York Times, 2014

“The History Of ‘Comfort Women’: A WWII Tragedy We Can’t Forget“ The Huffington Post Arts & Culture, 2013

“Spotlight on Women Artists at Incheon Biennale” The Korea Times, 2009

“Japan’s Forgotten WW2 Sex Slaves” Dazed & Confused Magazine, London, 2013

“Chang-Jin Lee exhibition opens at Wood Street Galleries” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2013

“The Comfort Women Speak” Taipei Times, 2013

Women News 여성신문 (Korean), 2017

Dutch “comfort women” survivors, and a former Japanese soldier (11 min)

The Comfort Women Museum, Taiwan, 2013

Brandeis University, Boston, 2019

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, Korea, 2017

Multimedia Collaborations, 2019-2021

BLOG – Research Trips to Asia (2008-2012)

This project is based on my interviews with survivors in 7 different countries, including Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Filipino, and Dutch “comfort women” survivors, as well as a former Japanese soldier from WWII.

COMFORT WOMEN WANTED brings to light the memory of 200,000 young women, referred to as “comfort women,” who were systematically exploited as sex slaves in Asia during World War II, and increases awareness of sexual violence against women during wartime.

The gathering of women to serve the Imperial Japanese Army was organized on an industrial scale not seen before in modern history. This project promotes awareness of these women, some of whom are still alive today, and brings to light a history which has been largely forgotten and denied.

The title, COMFORT WOMEN WANTED, is a reference to the actual text of advertisements which appeared in newspapers during the war. When there weren’t enough volunteer prostitutes through the ad campaigns, young women from Korea, China, Taiwan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Netherlands were kidnapped or deceived and forced into sexual slavery. Most were teenagers, some as young as 11 years old, and were raped by as many as fifty soldiers a day at military rape camps, known as “comfort stations.” Women were starved, beaten, tortured, and killed. By some estimates only 30% survived the ordeal.

Whenever there’s a war we hear about the suffering of soldiers, yet we hear almost nothing about the plight of women who are kidnaped and raped, or killed. Often it is the poorest and most marginalized elements of society who suffer most. Through out history women like this are too often invisible, forgotten and left with no place to turn.

The “Comfort Women System” is considered the largest case of human trafficking in the 20th century. Much in the same way that acknowledgment and awareness of the Holocaust helps to insure it will not happen again, by acknowledging this issue we can prevent another generation of enslaved “comfort women” from happening anywhere ever again.

Historian Suzanne O’Brien has written that

“the privileging of written documents works to exclude from history…the voices of the kind of people comfort women represent – the female, the impoverished, the colonized, the illiterate, and the racially and ethnically oppressed. These people have left few written records of their experiences, and therefore are denied a place in history.”

In the 21st century, human trafficking has surpassed drug trafficking to become the second largest business in the world after arms dealing. The “comfort women” issue illustrates the victimization which women suffer in terms of gender, ethnicity, politics, and class oppression, and how women are still perceived as a disposable commodity. This project promotes empowerment of these and all women, and seeks to establish a path toward a future where oppression is no longer tolerated.

On July, 2007, the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed H. Resolution 121, proposed by Mike Honda, Japanese-American Congressman, with 168 bipartisan cosponsors, calling for Japan’s acknowledgment of the sexual enslavement of “Comfort Women,” and acceptance of historical responsibility. Similar resolutions have passed in Canada, the Netherlands, the European Union, and Great Britain.

Despite growing awareness of the issue of trafficking of women and of sexual slavery as a crime against humanity, this particular history has gone largely unacknowledged. COMFORT WOMEN WANTED attempts to bring to light this instance of organized violence against women, and to create a dialogue by acknowledging their place in history.

Artworks

Ad-like Billboards, Kiosk Street Posters, Prints, Audio, Multichannel Videos, “Re-creation of a Military Comfort Station“

1) Ad-like Ad-like Billboards, Phone Booth Posters, MRT Subway Light Box Displays, and Prints in Multiple Languages:

The text COMFORT WOMEN WANTED is in black atop a red background. In the center are images based on historical photos of the Taiwanese, Korean, Chinese, Filipino, and Dutch women survivors when they were young, around the time of the war, juxtaposed with contemporary silhouettes of the now aged comfort women, in their current homes. One iconic image is of a Taiwanese “comfort woman” taken by a Japanese soldier during her enslavement. The images of the young women are surrounded by gold leaf, suggesting the halo of a saint from Renaissance painting, and honoring their courage in speaking out. Images of the elderly comfort women, by contrast, are empty silhouettes, and are intended to evoke a sense of loss. Of those who survived, many never went back home, or they were ostracized from their families and communities because of what was perceived as their “shameful past” in a conservative society cherishing women’s chastity as ideal. For most of these women, the sense of home was forever lost.

2) Audio and Multichannel Video Installation:

In the audio installation, two old fashioned telephones hang on either side of a red column referencing a phone booth. When people pick up a phone handset, they can hear the voices of “comfort women” survivors on one side which contrasts with the voice of a Japanese soldier on the opposite side. The installation creates the impression of a direct personal and intimate moment between the listener and the survivor.

3) Names and Songs:

At the entrance of the space, the actual names of women survivors are projected on a plaque on the floor, at the same time, the voices of the women singing their favorite traditional folk songs in multiple languages are heard. The projection of the names honors the women while the music creates a sense of universality.

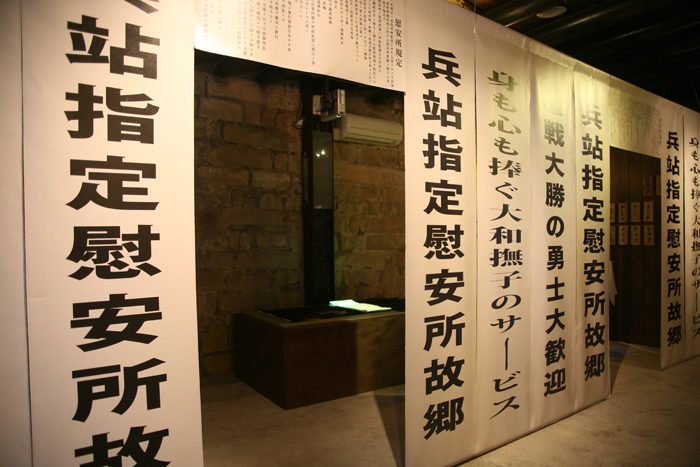

4) “Re-creation of a Military Comfort Station”:

The recreation of a comfort station is based on historical references including welcome and regulation banners, kimonos, tatami beds, washing bowls, windows, and Japanese name plaques. Videos of former comfort stations in Asia are projected on elements in the room.

Outside, welcoming and regulations banners are hung from floor to ceiling, creating fabric walls. During the war, banners at the entrances of military comfort stations welcomed and attracted soldiers. The written texts in Japanese said such things as “Homeland Military Designated Comfort Station,” “Japanese Girls Dedicating Their Hearts and Bodies in Service,” and “Grand Welcome to Victorious, Courageous Soldiers.”

Inside, videos of former comfort stations in Asia, including Dai Salon in Shanghai, the first comfort station ever, and former Indonesian comfort stations, are projected on individual elements in the room. On the walls are hung Japanese name plaques. Girls were forced to wear kimonos and use Japanese names. The recreation explores the idea of erased ethnic identity. The artificial made-up Japanese names which the women were forced to use contrasts with their real names at the entrance to the exhibit.

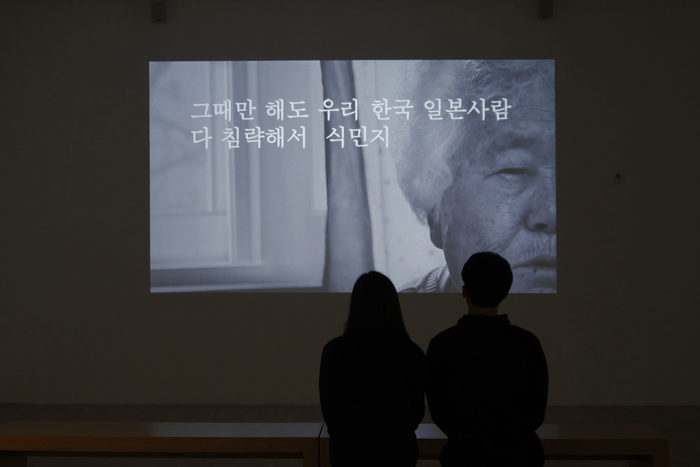

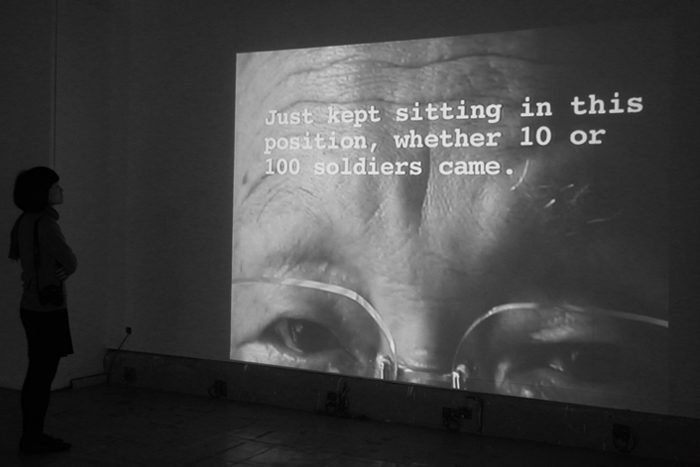

In the multichannel video installation, the Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Filipino, and Dutch “comfort women” survivors, and a former Japanese soldier talk about their experiences at the military comfort stations, as well as their everyday hopes and dreams, and who they are as people. The women also sing their favorite traditional folk songs in Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Filipino, and Dutch. This presents the women as individuals rather than as victims and highlights the experiences we all share, in order to put these monumental events in context. These are the stories and voices of the survivors.

Special Thanks

My deepest respect and admiration for all of

the courageous “comfort women” survivors I have met.

Korea: Yong-Soo Lee halmuni, Ong-lyeon Park halmuni, Oak-seon Yi halmuni. Gun-ja Kim halmuni, Oak-seon Park halmuni, Soon-ok Kim halmuni, Il-Chul Kang halmuni, Soon-Duk Lee halmuni, and Chun-hee Bae halmuni. Professor Jung Oak Yun, Professor Hyo Chae Lee, Professor Keum Hye Park, Professor Tae Guk Jun, Seoul Mayor Won Soon Park, Shin Kweon Ahn and The House of Sharing.

Taiwan: Shyou Fung Ho ahma, Hsiu-mei Wu ahma, Yang Chen ahma, Man-mei Lu ahma, Yin-Chiao Su ahma, and Hwa Chen ahma, Graceia Lai, Shu-Hue Kang, Huiling Wu, Li-Fang Yang, Margaret Shiu, Betsy Lan, Chi-Hsi Chao, and The Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation.

China: Wan Aihua dayang, Professor Zhiliang Su, and Professor Ye Chen,

Indonesia: Emah Kastimah, Marjiyah, and Eka Hindrati.

Australia: Jan Ruff O’Herne, Carol Ruff, Hannah Harborow, and Amnesty International Australia.

Japan: Yasuji Kaneko, Mina Watanabe, Alison Scott, Eriko Ikeda, Murayama Ippei, Georg Kochi, Misuzu Yamamoto, Hiroko Murata, Tatsuhiko Murata, and The Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace.

The Philippines: Nelia Sancho, Lola Julia Porras, Lola Fedencia David

USA: Congressman Mike Honda, Livia Straus, Barbara Corti, Marc Payot, Hali Lee, Angie Wang, Aiyoung Choi, Joyce Yu, Emily Colasacco, Wendy Feuer, Agnes Hsu, Bomsinae Kim, Charles Armstrong, Margaret Cogswell, Erin Donnelly, Felicity Hogan, Dai-Sil Kim, Ok Cha Soh, Bonnie Oh, Christine Choi, Aiko Miyatake, Agnes Bing Magtoto, Vera Chen, Jokotri Taro, Grace Qh Zhao, Phyllis Kim, Washington Coalition for Comfort Women, Teri Chan, Sandra Greuel, Soon Hee Lee, Chang Soo Lee, Steve Chang Wook Lee, Jeannie Kim Lee, Robert Clay, Paul Clay, and many others who have supported this project.

Supported by

The New York State Council on the Arts Grant

The Asian Women Giving Circle Grant

The Asian Cultural Council Fellowship

The Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s MCAF

The Korean American Community Foundation

The New York City Department of Transportation’s Urban Art Program